To start off this next post, I want to make a point: I'm starting to get more out of guests in the classroom than Solis. Let me repeat that: people I debated in high school are becoming the experts. Because social media can bridge a great deal of gaps, but it just can't make local culture obsolete. I tweeted not too long ago:

http://nyti.ms/ozAUbI the # compresses concepts; ext efficiency; obs linear typology; ret the acoustic; rev into iconography #mcluhan #wsusm

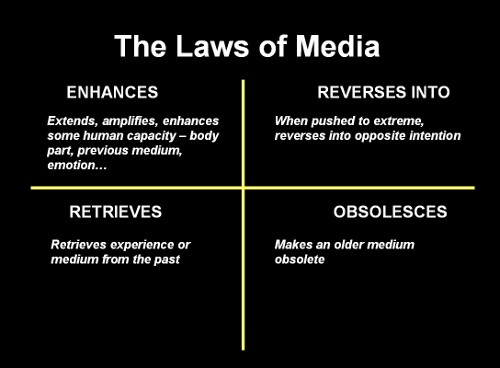

Marshall McLuhan is probably the most brilliant communications theorist I have come across. In another culture or age, he would either have been burned at the stake or praised as a prophet. His theory of media ecology took the high-brow work of Innis and Havelock and packaged it for the masses. His distinction between the linear, typographic worldview (acculturated to and from highly literate societies) against an acoustic, iconographic world (in the absence of some system of typography). Iconography and speech, like a radio station, broadcast meaning over time, adding context. Typography, in its higher forms, expects pragmatic layout, but is self-contained and rewind-able. He also noted a curious form called the Tetrad. Examine the following:

It's interesting that what does all of these things is the introduction and cultural assimilation of a communications technology. A new technology (say the wheel) extends an anatomic function (the feet in 360 degrees) enhancing the human's ability (to carry stuff long distances). The big distinction comes with the phonetic alphabet or other complex linear typographic distinctions. Once this occurs, new software can change the world. For instance, once literature became available a split in vernacular occurs between those whom can afford to read and those who can't, but even people from remote and separated tribes who can afford to read begin to have more in common with each other than people whom are living closer.

Other technologies, hardware like radios or satellite broadcasting bring whole nations and even the whole world together. The downside (or sometimes upshot) is that these technologies obsolesce other media artifacts. That's just in the physical, tangible world. In the realm of cultural anthropology, sociolinguistics, and Jungian psychology, retrieval and reversal are key. These occur as archetypes--the internet as a weapon retrieves the crossbow, for instance. Both are banned by the highest authorities and both turn untrained persons of even the lowest socioeconomic class into effective soldiers. Just a personal theory of mine, there. Reversal is what happens when something is overplayed--for instance, a song on the radio has the meaning when we first hear it and then a different one the millionth time. The horse, once the most important transportation tool--the tool that literally won the west--is now a recreation; a nostalgia. Kind of like people that still use MySpace as a tool to see how far they have come.

So I find it similarly interesting that posting such compressions of important information for audiences is bound to chronology. Something Scroggins and Beauchamp both noted when they presented. These guys are smart, empowered, and best of all--young. I'm kind of ready for a new dot.com boom as long as it isn't the same old blood that gets the riches. And these two definitely keep my hopes high. They get that if you don't understand the culture of the user (when they get on, what they click, what they avoid, etc.) then you don't understand how to make your social media campaign successful.

But where Scroggins and Beauchamp gave really interesting and contextualized information about social media and getting networks to perform the way a user wants, Solis has increasingly turned to making up words. The "egosystem," "twitter time," "now web," "statusphere," etc., etc., et... cetera... These didn't really help. Depending on where you're at, these might now make sense. But they are simple word play. Not worldly experience compressed into a concept.

And that's what I love most about twitter hashtags (those things that start with # and end in characters). The trend compresses information. A compressed ball of lead that weighs as much as a couch is ten times easier to carry than the couch, simply because of compression. Will Scroggins (mentioned earlier) talked about Cotweet, a brilliantly designed hashtag compilation application. This is a perfect example of how the hashtag extends human efficiency of labor in getting a message or conversation out. But because these messages are occurring in such a small space (10 or so characters) this obsolesces (completely for the first time) the typographic stress on strategic communication. We are getting so good at getting the idea across quickly and efficiently that my generation is giving up stock literacy for the kind of augmented secondary orality that Walter Ong describes in his works.

|

| If America's identity can be boiled down to a few symbols, why can't mine now that it doesn't take a million-dollar re-branding campaign? |

This retrieves that archetype the hippies and yippies of the sixties were seeking to revive by force: drop out of the book learning, tune in to the that acoustic, tribal drum beat. My generation, via the hashtag, is reversing into that the iconographic mindset (for better or worse), and though it would be easy to point to the Pepsi Generation's focus on corporate logos, these will never be embraced like the condensation of identity into your own personal hashtag: your @<name> on twitter. @ictsiege316 is CJ Schoch, the hashtag, for all intents and purposes. That is my flag for other sailors to see on the information superhighway--the surfers just see something flapping in the breeze. It's no surprise that literacy is decreasing in terms of actual literature, but people have no problem making it through Icefilms.info for Anons [ie: dummies] so that they can download the latest episode of Sons of Anarchy. For the record, a little attention to that link will save you a thousand dollars a year, or so. I could write that argument out, but I have a feeling that the iconogaphic link will fulfill it's role and make my point.

As such, I'd really like to end this post with a challenge. I pose this challenge because I'm at a brick-wall with objective reflection on the hypothesis. Prove the following statement wrong:

We can move ideas in mass communications faster and better with a hashtag or a hyperlink, than any other known alternative.